The word is “Therefore…” When you are making a deductive argument, this means that what you are about to say logically follows from (is implied by) what you have just said. That is, if the former part were to be true, what you’re about to say must also be true.

The word is “Therefore…” When you are making a deductive argument, this means that what you are about to say logically follows from (is implied by) what you have just said. That is, if the former part were to be true, what you’re about to say must also be true.

A non sequitur (Latin for: “it doesn’t follow”) is an invalid argument, one in which the premises don’t imply the conclusion, that is, where one could consistently accept all the premises and yet deny the conclusion.

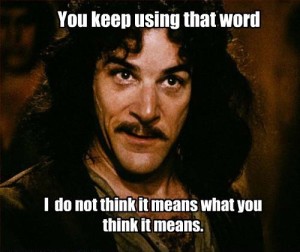

I recently stumbled upon this youtube video, The Trinity Explained (with Reason), featuring a supremely confident sounding young man. I watched amazed, as a torrent of non sequiturs ensued.

If only this fellow was as good at constructing arguments as he as at selecting pictures!

Here are most of them – note that in each case, the step starting with “Therefore” is not implied by the premises.

1. If unitarianism is true, God is more comprehensible than if trinitarianism is true.

2. God is not totally comprehensible and not fully explainable.

3. Therefore, unitarianism is false.

1. Unitarianism is true.

2. Therefore, God is no greater than a human being.

1. God is a spirit.

2. Angels are spirits.

3. Therefore, God is no greater than the greatest angel.

1. God created the angels.

2. God is greater than the angels.

3. Therefore, God is not (just) a spirit.

1. God is omnipresent.

2. Therefore, God is hyper-dimensional (exists in more than three dimensions).

1. Isaiah 40:28 is true.

2. Therefore, God exists in infinite dimensions.

1. A two-dimensional being would perceive a rotating cube as either contradictory or more than one object.

2. Therefore, humans can only think of the triune God as contradictory.

1. God is hyperdimensional.

2. Therefore, God is not a self.

1. We only need a tri-personal God, not one with more persons in him.

2. Therefore, God is only tri-personal.

1. A unitarian God couldn’t be all we need.

2. Therefore, it is false that there is a unitarian God.

But wait, there’s more. Most of the premises are (1) unargued for, (2) not obviously true (so they need to be argued for), (3) not more evident than his conclusion, (4) not things his opponents would grant.

All in all, a big heap of argumentative rubbish. The best I can say is that he is trying to argue for his views, and that he is speaking clearly enough to be refuted. These are laudable virtues, and not everyone has them, but they don’t make up for the fact that he’s asserting a pile of invalid arguments. Not to worry – youtube can help: watch 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d here.

Occasionally, he does hit on a valid argument, like this one towards the end:

1. God is omnipotent if and only if he is omnipresent.

2. A unitarian God can’t be hyperdimensional.

3. A being can be omnipresent only if it is hyperdimensional.

4. A unitarian God can’t be omnipresent. (2,3)

5. A unitarian God can’t be omnipotent. (1,4)

Yes, this is valid. IF 1-3 were true, then 4 and 5 would have to be true as well. Unfortunately, each of 1-3 has the four problems just mentioned. So the argument is worthless.

The moral of all this is: don’t commit this non sequitur:

1. The speaker seems very sure about what he or she is saying.

2. Therefore, the speaker is minimally competent in his or her subject matter.

or this one:

1. The speaker has given only worthless arguments for X.

2. X is false.

In both cases, 2 does not follow from 1!

The post The Trinity Explained (with Reason) appeared first on Trinities.